THEORY OF HOPE

Thomas Homer-Dixon

August 31, 2020

Note to reader: I originally prepared this document in 2018 and 2019 as a background study when I was developing the theoretical underpinnings of my argument about hope for my book Commanding Hope: The Power We Have to Renew a World in Peril. I have updated it for posting in August 2020.

Disciplinary Context

For over two millennia, philosophers, theologians, essayists, poets, and artists have devoted enormous attention to the phenomenon of hope. In philosophy, the treatments of David Hume, Immanuel Kant, and John Stuart Mill are especially important, as is the thought of Thomas Aquinas in Christian theology.1 My idea of hope—commanding hope—has roots in aspects of this thought, especially in Hume’s conception of hope as emotion and Mill’s insistence that imagination plays a critical role. But its closest intellectual cousins are ideas emerging from recent analytical philosophy and positive psychology.2

Analytical philosophy generally starts from the premise that hope is a mental state or, in the discipline’s terminology, a “propositional attitude” of the form “Sue hopes that p,” where “p” is a proposition (or statement) about a possible state of the world. It usually seeks to identify the necessary and sufficient conditions that must be satisfied for this mental state to exist; these conditions might be specific beliefs and emotions that the agent (Sue, in this case) must have regarding the state of the world identified by “p” for her mental attitude towards that state to qualify as “hope.”

Analytical philosophers often stipulate first principles or axioms and then use quasi-deductive argument to discern the principles’ consequences. Positive psychologists, in contrast, are more empirical and inductive. They concern themselves with “the application of psychology theory and methods to healthy cognition and human flourishing.”3 So, they generally study real people in social and controlled-laboratory settings to understand how, when, and where they experience what these psychologists define as hope.

My approach to understanding hope has much in keeping with modern analytical philosophy’s tight focus on how people’s hope is affected by their desires and by their estimates of whether those desires will be satisfied. It has much in keeping, too, with positive psychology’s focus on how people perceive their goals, possible pathways to those goals, and their capacity (agency) to pursue those pathways.4 Especially important here are perceptions of self-efficacy and “locus of control”—that is, whether external circumstances or internal choices are believed to determine one’s fate.5 Both the philosophical and psychological perspectives generally assume that the mental state of hope can vary in strength and has both emotional/motivational (desire) and cognitive (belief) elements.6

I have little time for what I’ve come to call “literary” invocations of hope. These are specious passages or aphorisms about hope that often make little logical or scientific sense, when examined closely, but circulate widely (often as posters on the internet) because of their immediate emotional appeal.7 They’re like a quick sugar high; and like a sugar high, they leave us feeling even emptier afterwards, because they have no enduring meaning. I believe that we must, instead, be more analytical about hope—to parse it and then rebuild it.

Commanding Hope's Seven Mental Components

In this context, commanding hope, as I define it, has seven key mental components.8 First, a person who experiences this type of hope has a specific idea of time—in particular, he or she believes that the future isn’t given and fixed but is instead creatively “open,” in the sense that it offers the possibility that people can create truly novel (i.e., not predetermined) alternative future worlds.9

Second, this person has the capacity for recursive imagination, and he or she can use this capacity to mentally visit some of those possible worlds.10 Note, though, that this capacity doesn’t mean the person can visit all possible worlds; many of these worlds, especially those that are truly novel, will remain unknown unknowns and unimaginable.

Third, the person has a set of values that can be used to evaluate and rank the desirability of the imagined worlds. These second and third components combine to create in the person’s mind both a set of imagined possible worlds and a preference ordering of those worlds.11 These components are common to all forms of “intentional” hope. Philosophers and psychologists use this term to refer to hope that has an object (a state of mind “oriented to some desired state of affairs which is believed to be attainable,” according to the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy), which is contrasted with “dispositional hope” or hope without an object (“a state of being hopeful”).12

The fourth component is a threshold of desirability. People hope for possible worlds that exceed such a threshold, because some futures are worthy of hope, and some are not. To have intentional hope, people must have such a threshold in their minds, even if it’s only implicit and fuzzy; and at least one possible world they imagine must be desirable, in the sense that the person would be willing to say: “I’d like that world to come to pass.”13 Generally, the stronger a person’s desire for a possible world, the stronger his or her hope for it.14

This desirability threshold relates directly to the concept of “enough” in the “enough vs. feasible” dilemma discuss in chapter 13 of Commanding Hope (pages 215 to 229). The type of hope that I call “commanding hope” focuses our imaginations on finding possible worlds where solutions to humanity’s critical problems are “enough”—where solutions make a real difference—because those worlds that don’t cross this threshold aren’t worthy of our hope.

The fifth component, again common to all forms of intention hope, is a set of rough estimates in the person’s mind of the probabilities that the desired worlds will come to pass; the set consists of one such estimate for each desired world.15 Analytical philosophers have long pointed out that we can’t hope for something we believe is truly impossible, while we won’t hope for something we believe is certain to happen.16 Generally, we hope for something only if we believe that the probability of its happening falls somewhere between these two extremes.17

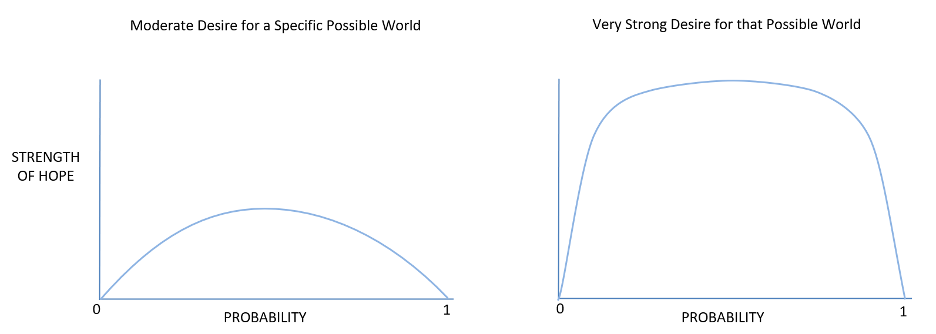

This fact suggests that the relationship between our estimate of the probability of a possible world and the strength of our hope for that world has an “inverted U” shape (see figure on the left below).18 I believe, further, that as the strength of our desire for that possible world rises, the sides of the inverted U become steeper, while the strength of our hope in the middle of the curve rises towards its maximum possible value (see the figure on the right below). In lay terms, when we desire a possible world intensely—for instance, when we desperately want someone we love to beat cancer—our hope will rise quickly to a very high level even if we know there’s only a small possibility of that outcome occurring; it will stay high across the entire range of probabilities, until we become convinced that the outcome is nearly certain to occur.

Again, we can see here a link to the enough vs. feasible dilemma. Commanding hope focuses our imaginations on finding possible worlds where solutions to humanity’s critical problems are “feasible.” A feasible solution is one where the probability of the future world in which that solution is implemented exceeds a certain threshold. That probability threshold, in turn, is commanding hope’s sixth key component.19

Note that I’m stipulating that a person with commanding hope, when deciding what actions should be pursued to address humanity’s critical problems, should have two thresholds in mind, even if those thresholds are only rough and intuitive: a desirability threshold, linked to a judgment about what would count as enough, and a probability threshold, linked to a judgment about what counts as feasible.

The seventh and last component is a set of beliefs in the person’s mind about the degree of control he or she has over whether desired futures will come to pass—a set of beliefs, in other words, about the degree of agency he or she can exert to change the likelihood that one or more of those possible worlds will be realized.

"Hope that" and "Hope to"

This last component’s role in hope is complex and so easily misunderstood. I find that a distinction between the locutions “hope THAT . . .” and “hope TO . . .” helps reveal these complexities (see pages 81 to 84 of Commanding Hope).20 “Hope THAT” is the propositional-attitude formulation philosophers commonly use. The phrase strongly implies that the person doing the hoping is passive and has little if any control over whether the desired possible world will come to pass. The locus of control over that world seems to reside in events and factors outside the agent. A good example is any statement of hope about the future’s weather, as when we say, “I hope that it will be sunny tomorrow.” We have no control over the weather, so our degree of hope for a sunny day tomorrow is entirely a function of our desire for that outcome and our estimate of its probability (based on something like weather reports).

The situation is very different when we use the “hope TO” locution, which is favored by some positive psychologists.21 The phrase is usually followed by a verb, immediately implying that the person doing the hoping expects to be actively engaged in trying to create the desired possible world and believes he or she has at least some degree of control over that outcome. So, the locus of control is at least partly internal to the agent. An example is a statement like “I hope to plant my vegetable garden tomorrow.” The person clearly believes he or she has some agency with regards to the outcome, but is uncertain about how much, perhaps because the weather might be bad.

With both “hope THAT” and “hope TO,” the person’s uncertainty plays a key role in his or her hope, but in the former it’s uncertainty about the occurrence of the future outcome itself, and in the latter it’s uncertainty about his or her degree of agency to produce that outcome.22

Indeed, hope only exists when there’s uncertainty. If, for instance, we’re certain that we can determine whether a particular desirable world happens, we won’t hope for it.23 To use a silly but nonetheless pertinent example, say I desire a possible world in the near future in which I’m eating a chocolate bar that’s currently sitting in our house’s fridge. If I have complete control over whether I go to the fridge, find the bar, and eat it, it makes no sense for me to say: “I hope to eat the chocolate bar.” On the other hand, if I suspect that my son Ben might eat the chocolate bar before I get to the kitchen (a real likelihood in our household), then my hope statement makes complete sense.

Uncertainty may be essential to hope, but a perception of agency isn’t, contrary to what many positive psychologists argue.24 We can “hope THAT” a desired possible world will come to pass, even as we believe we have no control over its likelihood. The positive psychologists are right, though, that a perception of agency is essential for us to “hope TO” bring about a specific possible world. Here, our perception that we have agency is a key input to our hope.25 Yet it’s an odd input, because it works only up to a point: to the extent we start to perceive that our agency is determinative—that we have complete control over the desired outcome—hoping for that outcome doesn’t make sense.26 (The Italian cognitive scientists Maria Miceli and Cristiano Castelfranchi call the “hope THAT” mental state “passive hope” and the “hope TO” mental state “active hope.”27)

Hope's Function

With this analysis of hope’s key mental components as a foundation, we can now usefully ask: What does hope do for us? In more technical terms, what is hope’s function? The biological, social, and psychological sciences often use functional explanations of the phenomena they study. These explanations have an intriguing property: the phenomenon in question is explained by reference to one of its outcomes or effects. Some people find such explanations puzzling, even suspicious, because they seem to suggest that an effect can loop backwards in time to become a cause. But functional explanations are now seen as entirely valid under well-specified conditions. For instance, when evolutionary biologists explain why members of a species have a particular anatomical feature, they often argue that the feature functions to help the species survive.28

We can apply the same kind of explanation to the existence of hope. Given the kind of high-level cognition that I’ve shown hope requires—imagining possible worlds, estimating probabilities and the like—hope is almost certainly unique to human beings. How might it have helped us survive as a species?

I believe that hope is among our most powerful psychological devices (along with various forms of denial) to overcome the otherwise potentially crippling despair and dread arising from our death anxiety. (See chapter 16, “Hero Stories,” of Commanding Hope, pages 274 to 286, for a discussion of the implications of this anxiety.) Hope, especially the “hope TO” version, gives us the impetus to persist and even thrive in the face of our conscious awareness of certain annihilation. We can’t hope to avoid death itself, of course, because our control over this final threat is limited, at best, to postponing its arrival a bit. Instead, as the social psychologists who have developed Terror Management Theory argue, we invest our hope in immortality projects that we define and understand through our hero stories.29 In these stories we imagine we have some control over—some real agency regarding—which future worlds will arise, and in those worlds some part of us avoids annihilation.

The Princeton scholar Philip Pettit has made a similar argument, but without the Terror Management Theory underpinnings. What Pettit calls “substantial hope,” which he contrasts with “superficial hope,” is an essential source of human motivation and ultimately personal identity and agency in a frightening and disheartening world. This kind of hope, he says, lifts us out of “the panics and depressions to which we are naturally prey and [gives] us firm direction and control.”

Without hope, there would often be no possibility for us of asserting our agency and of putting our own signature or stamp on our conduct. We would collapse in a heap of despair and uncertainty, beaten down by cascades of inimical fact. Hope . . . can be our one salvation as agents and persons, our only way of remaining capable of seeing ourselves in what we do.30

Agency's Dual Role

We see here another, and vitally important, aspect of the relationship between hope and agency. While hope doesn’t require agency—and in fact high agency with respect to future outcomes may make hope nonsensical—hope often motivates agency. In tough times, hope keeps us going; it encourages us to persist in trying to expand our agency and bring the world around us under our control, as much as we can. Pettit goes on: “[When] people do not despair under bad news or in evil times—when they manage to keep their hearts up and press on in positive ways—they often succeed in overcoming obstacles that might otherwise have brought them down.”31

Critically, then, in situations where we might “hope TO” bring about a particular future, our agency is both an input to, and an output of, our hope.32 This dual role creates the possibility of positive feedbacks—or in the vernacular, of either virtuous or vicious circles—in our psychology of hope.

In the virtuous circle, our perception of our agency, likely derived from memories of having successfully exercised our agency in the past to achieve something we desired, becomes an input to our present hope, which then encourages us to exercise our agency vigorously to produce a desired possible world in the future. Experience of new success then creates a memory that’s an input to our hope in the future. But in the vicious circle, our memories of past situations of very limited agency cause us to forgo trying to change things to bring about desired possible worlds in the future, an outcome that only lays down more memories of limited agency, and weakens our future hope. Positive psychologists pay attention to such feedbacks and try to manipulate them to prevent hopelessness and build hope.33

The Tension at Hope's Core

If hope’s main psychological function is to motivate us to persist through our hardships and, ultimately, to overcome and even sublimate our fear of death, then we have a lot of incentive to sustain it—to keep it healthy and as powerful as possible. This means, in turn, that we’ll want to keep ourselves somewhere near the top of the inverted U, or somewhere in the middle of the probability spectrum between the extremes of impossibility and certainty.

The result is a fundamental tension at hope’s core. On one hand, to have hope we need to stay away from the “zero lower bound” of probability. So, we have an incentive to select or distort data about reality to sustain a meaningful probability in our minds that our desired possible world can come to pass. On the other hand, we don’t want to be so successful in creating this selective reality that we push ourselves to other end of the probability range, convince ourselves that the outcome we want is certain, and lose hope’s motivating power.

Scholars who study hope struggle with this tension’s implications, especially with the idea that sometimes a person’s need to maintain hope justifies his or her willful misperception of reality.34 The renowned positive psychologist C.R. Snyder highlights this struggle in a revealing passage in one of his earliest articles:

In my clinical psychology graduate student days, I learned that the accurate perception of reality was the cornerstone of psychological health. Likewise, the surrounding 1960s echoed the importance of reality in such phrases as “Tell it like it is” and “Get real.” Some 15 years later I was sitting with a psychotherapy client who was pondering his plight. He grumbled, “What's so great about reality?” Although this rhetorical question obviously flew in the face of my education in regard to the virtues of reality, it had a ring of truth to it. Indeed, in the last several years I have explored the processes by which people “negotiate” with their realities, and I have become convinced that total accuracy in the perception of oneself and one's life events is not necessarily adaptive.35

The problem for hope in our world today is that the stubborn facts of our global reality—of climate change, pandemics, worsening economic inequality and instability, rising authoritarianism, increasing danger of nuclear war, and growing mass migrations—are forcing us towards the lower bound, towards believing that future worlds worthy of hope are impossible. So, in our desperation to maintain some room for hope, we’re increasingly ignoring those facts or telling ourselves the situation isn’t so bad. This behavior no longer resembles Snyder’s psychologically healthy “negotiation” with reality; rather, it has become pathological and destructive self-deception.36

Commanding Hope's Three Defining Properties

Commanding hope directly confronts this challenge by being simultaneously honest, astute, and powerful. I’ll consider each of these three properties in turn.

Honest Hope:

Commanding hope insists—first and foremost—that we be honest with ourselves about the dire challenges humanity faces, including the likely immutable slow processes that will channel and constrain our collective future, sharply limiting the range of desirable possible worlds available to us (as outlined in chapter 9 of Commanding Hope, “The World to Come Today,” pp. 144 to 165). It advocates neither optimism nor pessimism about these facts, but rather clear-eyed realism. As the American professor of environmental studies and politics David Orr writes, the hope we need is “made of sterner stuff than optimism.”

To understand why, we must identify the difference between optimism and hope. I define optimism as a generalized perceptual bias. It’s a person’s general tendency to select data in a way that shifts the perceived probabilities of what he or she regards as “good” outcomes higher.37 Pessimism, in contrast, is a general tendency to select data in a way that shifts the perceived probabilities of “bad” outcomes higher. But hope, as we’ve seen, is a mental attitude of desire towards a specific imagined world (usually in the future); it’s this explicit desire, coupled with an implicit probability estimate of that outcome, that makes it “hope.”

So, one’s hope is distinct from one’s general tendency towards optimism, pessimism, or realism; it’s also significantly, though not entirely, causally independent of that tendency. We don’t need optimism to be hopeful. In fact, optimism, taken to an extreme, can cancel out hope, by raising the probability of a desired outcome to certainty, which makes hope unnecessary. On the other hand, we can be hopeful pessimists—although the stance sounds a bit odd—as long as our pessimism doesn’t drive our estimated probability of the desired outcome to zero.

Commanding hope’s clear-eyed realism means that it has, at its core, a commitment to truth.38 It assumes we inhabit a discernable reality, that we can adjudicate among claims about this reality by reference to empirical evidence, and that some claims about this reality are more accurate or “true” than others. It holds that “truth,” therefore, is a meaningful, defensible, and useful concept.

Then, commanding hope adopts a specific moral stance towards that truth: it holds that seeking to discern the truth and accepting its full implications are morally good behaviors.39 This stance is anchored in the following pragmatic consequentialist logic: while sometimes shading the truth—selecting or distorting data to make the world look more positive—might help sustain or boost our hope and encourage our sense of agency, with regards to humanity’s critical global problems these behaviors are dysfunctional, because the costs of the resulting poor preparation, planning, and engagement with the problems outweigh the benefits of any extra hope and motivation thus derived. As Orr argues, we can find the hope we need today only “in our capacity to discern the truth about our situation and ourselves and summon the fortitude to act accordingly.”40

Moreover, Orr says, that truth, even if it’s brutally harsh, doesn’t have to undermine our agency; it can even invigorate it. Citing Abraham Lincoln’s appeals against slavery, Winston Churchill’s calls to the British people to defeat Nazism, and everyday people facing and overcoming life-threatening illness, he argues that telling the truth can summon people “to a level of extraordinary greatness appropriate to an extraordinarily dangerous time.”41

Astute Hope:

Honest hope seeks and accepts the truth about the future’s challenges, constraints, and dangers. It’s an essential property of commanding hope, but it’s not enough. If our hope is to generate the motivation we need to push through adversity, it must also incorporate a clear sense of where we want to go and how to get there. In short, it must be astute.

Here the positive psychologists’ insights are enormously useful. These researchers show that for people to have powerfully motivating hope, they must have a clear goal—in our terms, a desired possible world—and perceive at least one feasible “pathway” to get there. A pathway is a plan that visualizes a set of actions that should be carried out in specific stages to reach the goal.42

Any such plan is, essentially, a rough-and-ready recipe or set of instructions that indicates what should be done with what resources and tools (both material and social) at what times to achieve the desired goal. It needs to draw on the best available knowledge about present and future constraints, opportunities, and dangers. It will likely have gaps, because at the start of the pathway especially, knowledge will be incomplete; it will almost certainly have to be revised on the fly as circumstances change.

But one feature is key when we’re trying to address our collective global problems. Astute hope must be strategically smart. It must be informed by a deep understanding not only of our own perspective on the world—our worldview—but also of the worldviews of others we’ll encounter along the pathway, be they friends, potential allies, or perhaps implacable opponents. (See Commanding Hope, chapter 17, “Strategic Intelligence,” pp. 287-297.) Then it must exploit this understanding to incorporate into its goals and plans judgements about possible strategic interactions with these other actors—about how our actions are likely to be perceived by them, how they’ll likely respond, and how we should adjust our actions now in anticipation of their likely responses.43

This is why I argue in Commanding Hope that the state-space model and cognitive-affective mapping can be valuable tools for sustaining our hope (see, especially, chapter 18, “Mindscape” and chapter 19, “Hot Thought,” pages 298-330). For our hope to be astute, our plans must be strategically smart; and for our plans to be strategically smart, we must be able, as much as possible, to see the world as others see it—to “get inside” their minds, so to speak—and then act accordingly. Deep understanding of ourselves and others, and of how our worldviews might mesh together or clash as we contest and try to build the future, is an essential ingredient of the hope we need.

Powerful Hope:

Each of commanding hope’s three defining properties has a fundamentally distinctive character. Its honesty is a moral property; it concerns the moral stance that people who hold this kind of hope should have towards the truth. Its astuteness is an epistemological property; it concerns how and what people with this kind of hope must know to be effective in reaching their desired future. Finally, commanding hope’s power is a psychological property; it concerns the type and strength of motivation this hope provides.

Powerful hope galvanizes our agency—our capacity, as I say in the book, to “discern our most promising paths forward and choose among them.” Our agency doesn’t guarantee we’ll reach our desired destination—the future possible world we most favor—but it’s a sine qua non, a necessary condition, for that good outcome.

For hope to have this motivating force, we need to create a virtuous circle—what complexity scientists call a positive feedback loop—linking our worldviews, our vision of the future, and our hope (see Commanding Hope page 54). This circle must operate in both our minds and in the world that we’re trying to change. We can initiate the circle by imaging together—even “designing” together using the kind of tools I describe in the book—worldviews that are alternative to those dominant today. These will provide the first scaffolding for a shared, transformative vision of the future centered on principles of opportunity, safety, justice, and a species-wide feeling of “we-ness.” This vision can then become the clear motivating object that powerful hope requires, by allowing people around the world to weave together, into a compelling global narrative, their complementary hero stories. And this hope will, in turn, galvanize our agency to continue the hard work of imagining and implementing positive worldview change.44

Concluding Remark

Commanding hope’s three properties are interdependent. Hope can’t be astute if it’s not honest: we won’t develop the clear plans astute hope requires, if we’re not honest with ourselves about the challenges we face; indeed, we mightn’t develop any plans at all. And hope can’t be powerful if isn’t astute: to have powerfully motivating hope, we need a keen sense of agency, and a keen sense of agency requires that we have a clear plan to create the possible world we desire.

Footnotes

1 For a summary of these thinkers’ ideas about hope, see J. P. Day, “Hope,” American Philosophical Quarterly 6, No. 2 (April 1969): 89-102. While Day’s summary is excellent, his critical assessment is now substantially incorrect, considering the findings of modern cognitive and brain science.

2 In analytical philosophy, see R. S. Downie, “Hope,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 24, No. 2 (December 1963): 248-251; Day, “Hope”; Luc Bovens, “The Value of Hope,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 59, No. 3 (September 1999): 667-81; Philip Pettit, “Hope and Its Place in Mind,” Annals AAPSS 592 (March 2004): 152-65; Ariel Meirav, “The Nature of Hope,” Ratio 22 (2009): 216-33; and Bekka Williams, “The Agent-Relative Probability Threshold of Hope,” Ratio (new series) 26 (2 June 2013): 179-95. On positive psychology, the most important pioneer of research on hope in this field is C.R. (“Charles”) Snyder; for an overview of his “hope theory,” see Snyder, “Hope Theory: Rainbows in the Mind,” Psychological Inquiry 13, No. 4 (2002): 249-75. Important research has also been conducted in cognitive neuroscience on the relationship between phenomena such as childhood abuse, post-traumatic stress disorder, and schizophrenia and the neurological correlates of hope; see, for instance, Michael De Bellis, “Biologic Findings of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Child Maltreatment,” Current Psychiatry Reports 5 (2003): 108-117. A recent study of the neurobiological bases of hope is Song Wang, Xin Xu, Ming Zhou, Taolin Chen, Xun Yang, Guangxiang Chen, and Qiyong Gong, “Hope and the Brain: Trait Hope Mediates the Protective Role of Medial Orbitofrontal Cortex Spontaneous Activity against Anxiety,” NeuroImage 157 (2017): 439–447.

3 Travis Lybbert and Bruce Wydick, “Poverty, Aspirations, and the Economics of Hope,” Economic Development and Cultural Change (November 2017), DOI: 10.1086/696968. For an overview of the field, see Jeffrey J. Froh, “The History of Positive Psychology: Truth Be Told,” NYS Psychologist 16, No. 3 (2004): 18-20.

4 This formulation is due to Snyder. See “Hope Theory”; and Snyder, et al., “The Will and the Ways: Development and Validation of an Individual-Differences Measure of Hope,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 60, No. 4 (1991): 570-85.

5 Albert Bandura, “Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change,” Psychological Review

84, No. 2 (1977): 191-215; and Julian B. Rotter, “Generalized Expectancies for Internal Versus External Control of Reinforcement,” Psychological Monographs: General and Applied 80, No. 1 (1966): 1-28.

6 This distinction between hope’s motivational and cognitive processes also appears in neurological studies that highlight the roles in optimism (a psychological bias) of the amygdala (in emotional processing) and the frontal cortex (in cognitive functions); see Bojana Kuzmanovic, Anneli Jefferson, and Kai Vogeley, “The Role of the Neural Reward Circuitry in Self-referential Optimistic Belief Updates,” NeuroImage 133 (2016): 151–162.

7 An example is the late Czech statesman and writer Václav Havel’s oft-cited comment: “Hope is not the same thing as optimism. It is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out.” In these sentences, Havel sets up a strawman contrast between optimism (simplistically defined) and hope, and then grounds his definition of hope in a notion of “making sense” that itself has no foundation. To be fair, Havel’s words are extracted from an interview in which he was clearly exploring—and struggling to articulate—his partially formed thoughts about hope (see https://www.vhlf.org/havel-quotes/disturbing-the-peace/). The full passage suggests that Havel’s idea of hope resembled the “conviction that something like . . . a compelling moral, normative, or spiritual framework will guide and protect us and give our lives meaning” that I discuss on page 78 of Commanding Hope.

8 I regard each of these conditions as necessary and together as jointly sufficient for commanding hope.

9 Because the future is open, these possible worlds don’t already exist; in other words, commanding hope doesn’t require the proliferation of parallel universes that theories in modern physics often propose to cope with the implications of quantum indeterminacy. I discuss the idea of the open future, and specifically the thinking on this issue of the physicist Lee Smolin, in Commanding Hope, pages 106 to 110.

10 Hope doesn’t always relate to future possible worlds: a person can hope that a given state of affairs holds in the present (or held in the past), as in “I hope it’s sunny now in Barbados.” In such cases, the speaker is simply ignorant of features (for example, whether it’s sunny in Barbados) of the world that he or she happens to inhabit (or happened to inhabit, in the past). On recursive imagination, see Commanding Hope, pages 94 to 98, and Michael Corballis, The Recursive Mind: The Origins of Human Language, Thought, and Civilization (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011). On the neurological basis of recursive thinking, episodic memory, and imagining the future, see Daniel Schacter and Donna Rose Addis, “The Optimistic Brain,” Nature Neuroscience 10, No. 11 (2007): 1345-1347; and Schacter, Addis, and Randy Buckner, “Episodic Simulation of Future Events: Concepts, Data, and Applications,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1124 (2008): 39–60.

11 These possible worlds might be interdependent (or mutually exclusive), in the sense that realizing one might require (or preclude) realizing another. Joseph Godfrey analyzes such interdependencies among hoped-for states in A Philosophy of Human Hope (Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff, 1987), pp. 57-61.

12 Philip Stratton-Lake, “Hope,” in Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, general ed. Edward Craig, vol. 4 “Genealogy to Iqbal” (London: Routledge, 1998), p. 507. I discuss dispositional or “objectless” hope on page 78 of Commanding Hope; among the prominent exponents of this kind of hope are the philosophers Gabriel Marcel, Joseph Godfrey and Jonathan Lear. On intentional versus dispositional hope, see also Derek Edyvane, Civic Virtue and the Sovereignty of Evil (New York: Routledge, 2013), p. 125. “Intentional hope is associated with the destination, the end and purpose of our striving, whilst dispositional hope, or hopefulness, is associated with the journey and with our striving itself.”

13 This threshold of desirability is distinct from a person’s more general value system, because it’s a meta-value—a preference for certain preferences.

14 Godfrey provides a comprehensive treatment of “hope’s desiring” in chapter 3, “Hoping, Desiring, and Being Satisfied,” of A Philosophy of Human Hope, pp. 15-25. Cognitive scientists sometimes refer to hope as a type of “anticipatory representation.” See Maria Miceli and Cristiano Castelfranchi, “Hope: The Power of Wish and Possibility,” Theory & Psychology 20, No. 2 (2010): 251-76.

15 The recognition that hope involves both desire for a particular future state and an estimate of that state’s probability is not new. For instance, both Thomas Aquinas and Thomas Hobbes formulated their understandings of hope in these terms, with Aquinas writing that “the object of hope is a future good, difficult but possible to obtain” and Hobbes stipulating that “‘appetite,’ with an opinion of obtaining, is called ‘hope.’” See Aquinas, Summa theologiae, First Part of the Second Part: L.40, C.6, “Article 5: Whether experience is a cause of hope? at http://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/03d/1225-1274,_Thomas_Aquinas,_Summa_Theologiae_%5B1%5D,_EN.pdf; and Hobbes, Leviathan Chapter 6, “Of the Interior Beginnings of Voluntary Motions; commonly called the passions; and the Speeches by which they are expressed” (London: Routledge, 1886), p. 33.

16 Downie, “Hope,” pp. 248-49; and Bovens, “The Value of Hope,” pp. 673-74. These assumptions are central to what philosophers commonly call the “standard account” of hope; see Meirav, “The Nature of Hope,” and Williams, “The Agent-Relative Probability Threshold of Hope.” The mental component of probability estimates distinguishes hoping from wishing. A wish is a statement of desire for a counterfactual state in the present or an imagined future world that has no probability assigned to it. One can and often does, for instance, wish for imagined worlds’ that are clearly impossible (as in “I wish I could fly like a bird”).

17 Based on years of empirical research, the positive psychologist C.R. Snyder offers two caveats: people who have a strong, agential sense of hope, whom he calls “high-hope persons,” will sometimes intentionally introduce uncertainty into an otherwise certain prospect (by, for example, setting a time limit on the completion of a task), perhaps to “stretch their skills”; other times, they might insist on pursing goals that seem unattainable, and occasionally succeed in attaining them. “I have learned that high-hope people occasionally alter those seeming absolute failure situations so as to attain the impossible. Over the years, for example, one of my favorite laboratory tasks has involved the solving of anagrams. In that regard, I had developed some anagrams that were so complex that they had not been solved in any of my previous experiments. These anagrams, I thought, represented virtual impossibilities for success. More recently, however, very high-hope people have been solving some of these previously unsolvable anagrams. The seemingly unreachable, therefore, may become reachable.” See Snyder, “Hope Theory,” pp. 250-51.

18 See J.R. Averill, G. Catlin and K.K. Chon, Rules of Hope (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1990), pp. 13, 16, and 33 for empirical evidence in support of this claim. After studying the subjective experience of hope of 150 undergraduate students, the authors conclude that “the objects of hope tend to fall in the middle range of probabilities,” which they find to be about 58 percent. In the 1950s, the American psychologist John Atkinson identified a similar—and likely causally related—inverted-U relationship between a person’s subjective assessment of the probability of success in completing a task (a function of the task’s difficulty) and the strength of the person’s motivation to achieve success in that task. See John W. Atkinson, “Motivational Determinants of Risk-Taking Behavior,” Psychological Review 64, No. 6 (1957): 359-72.

19 Williams argues correctly, I believe, that this probability threshold is “agent-relative,” by which she means that it varies across people according to their psychological and social characteristics. Hoping for a possible world that has a probability below this threshold is “pointless.” See Williams, “The Agent-Relative Probability Threshold of Hope.”

20 This distinction was first examined in Downie, “Hope.”

21 Lybbert and Wydick, “Poverty, Aspirations, and the Economics of Hope.”

22 Philosophers and psychologists who study hope use the term “uncertainty,” as I do here, to mean both a person’s estimate of the probability of a particular outcome, which must be greater than 0 but less than 1 for a person to be “uncertain” about that outcome, and also their perception of their degree of ignorance in making the probability estimate. The former is what economists, statisticians, and probability theorists generally call perceived “risk,” while the latter is a component of what I’ve called “deep uncertainty” in chapter 6 (p. 104) of Commanding Hope.

23 “A strong confidence about p’s occurrence or one’s ability to bring it about leave little room to hope.” See Miceli and Castelfranchi, “Hope: The Power of Wish and Possibility,” p. 257.

24 Ibid., pp. 257-58.

25 “[We] hypothesize that hope is fueled by the perception of successful agency related to goals. The agency component refers to a sense of successful determination in meeting goals in the past, present, and future.” Snyder, “The Will and the Ways,” p. 570.

26 Stan van Hooft, Hope (Oxford: Routledge, 2014), p. 35.

27 See Miceli and Castelfranchi, “Hope: The Power of Wish and Possibility,” pp. 265-68.

28 Of course, not all features of biological, social, and psychological systems have a function. In some cases, for instance, the features may be vestigial (i.e., left over from earlier evolution and no longer functional) or accidental.

29 For a survey, see Tom Pyszczynski, Sheldon Solomon, and Jeff Greenberg, “Thirty Years of Terror Management Theory: From Genesis to Revelation,” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 52 (December 2015): 1–70.

30 Pettit, “Hope and Its Place in Mind,” pp. 160-61. Similarly, Miceli and Castelfranchi write: “[Hope’s] basic ingredients—a mere belief of possibility about an event p, together with a goal or wish that p occurs—endow hope with some special properties, such as its greater resistance to disappointment, as well as, when disappointment occurs, its greater resilience in comparison with positive expectation.” See Miceli and Castelfranchi, “Hope: The Power of Wish and Possibility,” p. 255.

31 The cognitive neuroscientist Tali Sharot makes a similar point about optimism. Optimism, she suggests, serves as a self-fulfilling prophecy that increases the probability of positive future outcomes. See Sharot, The Optimism Bias: A Tour of the Irrationally Positive Brain (New York: Pantheon Books, 2011).

32 Political scientist Manjana Milkoreit discusses this dual role in Mindmade Politics: The Cognitive Roots of International Climate Governance (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT, 2017), pp. 169-70.

33 “If . . . high-hope people are in a positive cycle regarding self-referential thinking, then it also can be said

that low-hope people may find themselves in a ‘wheel of misfortune.’” See C.R. Snyder et al., “Preferences of High- and Low-hope People for Self-referential Input,” Cognition and Emotion 12, No. 6 (1998): 807-23, especially 822. Also: “[We] have found that high-hope people embrace such self-talk agency phrases as, "I can do this," and "I am not going to be stopped." See Snyder, “Hope Theory,” p. 251.

34 Pettit argues that hope involves “setting aside doubts” about the likelihood of the desired outcome. But to my mind, he ties himself in a knot trying to establish that this process is rational and benign. “Hope, it is true, will display some facets that are reminiscent of self-deception. If I set out to act on a certain hope, for example, I may tell you that I do not want you to take me through this or that litany of evidence and fact. I may recognize that the hope around which I am organizing my attitudes and actions is a frail reed that needs nurturing and that it may not survive your recitation. But in recognizing that this is so, and in refusing to listen to the full recital of presumptive evidence, I do not tell myself a lie. I can be utterly undeceived about what I am doing.” See Pettit, “Hope and Its Place in Mind,” p. 162. Miceli and Castelfranchi offer an interpretation of agential hope (what they call “active hope”) that doesn’t require “altering likelihood estimates.” See “Hope: The Power of Wish and Possibility,” pp. 266-68.

35 Snyder, “Reality Negotiation: From Excuses to Hope and Beyond,” Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 8, No. 2 (1989): 130-57, especially p. 130.

36 “[The] distortion of reality to the delusional level is a hallmark of schizophrenia, delusional disorder, mood disorders with psychotic features, and so on.” Snyder, “Hope Theory,” p. 265.