Cognitive-affective mapping (CAM)

Introduction

Cognitive-Affective Maps (or CAMs for short) are diagrams of the connections between concepts that depict the content of a person’s or group’s belief system. Cognitive maps—also known as conceptual graphs, concept maps, or mind maps—have long been used in psychology and political science to visualize how people represent important aspects of the world and to identify distinct patterns in decision making. Cognitive-Affective Maps are innovative in part because they incorporate emotion directly into such a representation of beliefs, in recognition of the scientific finding that the emotional values attached to concepts, far from being hindrances to rational thought as often assumed, are in fact indispensable elements of human perception, understanding, and decision making. CAMs are also innovative because they discriminate between two types of relationships between concepts.

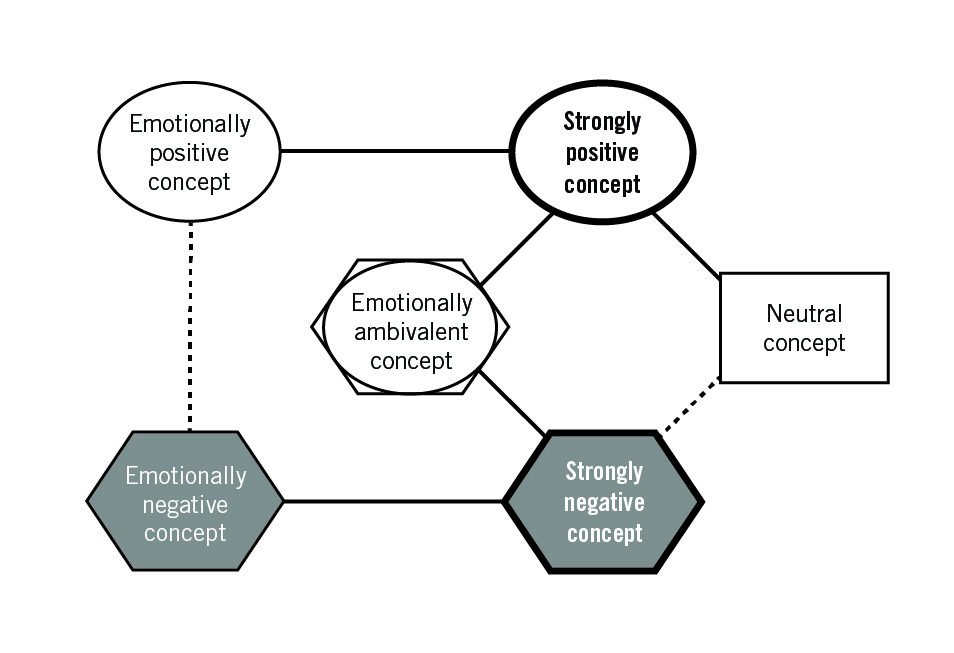

CAM represents a belief system as a network of concepts, using shapes to represent concepts and lines to represent relations between concepts:

- Ovals represent emotionally positive (pleasurable) concepts;

- hexagons represent emotionally negative (painful) concepts;

- rectangles represent concepts that are emotionally neutral; and,

- an oval superimposed on a hexagon indicates ambivalence (a single concept that can generate simultaneous or alternating positive and negative emotions).

- The thickness of a shape’s lines represents the relative strength of the positive or negative value associated with it.

- If color is available, ovals are green (go), hexagons are red (stop), rectangles are yellow, and superimposed ovals/hexagons are purple.

- A solid line represents a concordant or mutually supportive relationship between two concepts;

- a dashed line represents a discordant relationship between two concepts—that is, a relationship of mutual tension; and,

- the thickness of the line indicates the strength of that emotional link.

Before starting, a person constructing a CAM must have a body of evidence from which to draw inferences about the subject’s beliefs and emotions. This evidence might be no more than personal experience with the subject that allows the development (in the form of a CAM) of a provisional hypothesis about the subject’s beliefs. But one of the benefits of this method is that it allows for input from a variety of sources. Maps can also be derived from analysis of texts and from survey or interview data, and they can even be drawn by the subjects themselves.

Why CAMs Are Useful

CAMs allow researchers to treat ideas as units of data—empirical evidence—that can be used to test specific claims about the nature and function of belief. They represent the centrality of emotion in any decision process. Deep understanding of people’s beliefs often requires a representation of emotion that captures more than merely positive versus negative valence; CAMs alone cannot, for example, draw out the significant differences between positive emotions of, say, happiness, pride, exuberance, and contentment and negative emotions such as anger, hate, jealousy, disgust, frustration, and contempt. Yet even CAMs one-dimensional representation of emotion can capture a great deal of a belief system’s emotional complexity, and therefore of its essential character, by showing how the system’s overall emotional coherence contributes to its function and stability.

Emotional coherence is crucial to problem solving or decision making. In a CAM, not only does each concept have an emotional valence, but any one concept’s emotional valence also affects the valences of the other concepts to which that concept is linked. For a belief system to be stable, the overall pattern of emotional relationships in the concept network must be coherent. (For a full discussion, see Thagard, 2006.) If the belief system does not exhibit emotional coherence, it will adjust until it does. For instance, if new information is introduced in the form of new concepts, new links between concepts, or changes to the emotional valences of existing concepts, the network will adjust itself until it is again coherent.

Cognitive-Affective Maps are accessible to anyone, without specialized background knowledge. CAMs can help an analyst quickly visualize how a belief system functions and how that system influences a person or group’s action. For instance, they can help mediators intervening in a dispute quickly recognize why certain concepts may be emotionally provocative to different parties or how each side perceives the other’s viewpoint (Homer-Dixon, et al., 2014). They can also show how a notion that may seem nonsensical to outsiders or out of sync with objective reality is powerful and durable to those who possess it, because it is integral to the belief system’s overall coherence. And they can help researchers, mediators, activists, and the lay public understand how seemingly small changes to a person or group’s belief system—such as exposure to new concepts—might affect its emotional coherence, triggering cascades of changes to the whole belief system.

Explanation of Terms

Concept: In CAMs, a concept is a mental representation of an object in the world, in the form of a symbol or signifier, in this case usually a word or short phrase. The object may be abstract in nature, but it must be represented by a noun or noun phrase, not, say, an adjective. For example, in a CAM “happiness” can be a concept; “happy” cannot. Our approach treats concepts as the constitutive elements of belief; beliefs are composites of concepts in the way that sentences are composites of words.

Value (emotion): Almost all concepts activated in the mind come with an emotional response, like fear, anger, hope, and love. While in reality there are complex nuances to the nature of this emotional response, for the purpose of providing a rough model of a belief system’s emotional coherence, CAMs reduce these responses to four categories:

- Positive: the concept induces a good feeling.

- Negative: the concept induces a bad feeling.

- Neutral: the concept activates little if any feeling, but it is a place-holder connecting other concepts.

- Ambivalent: the concept can instigate strong feelings, but that feeling may be either positive or negative, depending on the circumstances of its activation. Ambivalent concepts usually signal that an underlying composite belief should be further unpacked to explain the implied contradiction.

Links: In CAMs, links indicate that two concepts are associated in the mind of the individual or group, and that the emotional valence of one tends to affect the valence of the other, in either direction or both. A solid line represents a felt sense of emotional concordance, support, or compatibility between the two concepts. Usually this means that both produce the same (positive or negative) emotional reaction. A dashed line represents emotional discordance, tension, or opposition. Usually this means that the concepts produce opposite emotional reactions.

Select Bibliography

Findlay, S. D., & Thagard, P. (2014). “Emotional change in international negotiation: Analyzing the Camp David accords using cognitive-affective maps”. Group Decision and Negotiation, 23, 1281-1300.

Homer-Dixon, T., Milkoreit, M., Mock, S., Schröder, T., and Thagard, P. (2014). “The conceptual structure of social disputes: Cognitive-affective maps as a tool for conflict analysis and resolution,” SAGE Open.

Homer-Dixon, T., Leader Maynard, J., Mildenberger, M., Milkoreit, M., Mock, S., Quilley, S., Schröder, T., and Thagard, P. (2013). “A complex systems approach to the study of ideology: Cognitive-affective structures and the dynamics of belief change,” Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 1(1): 337–363.

Milkoreit, M. and Mock, S. (2014). “The networked mind: Collective identities as the key to understanding conflict,” Chapter 8 in Networks and Network Analysis for Defense and Security, ed. Masys, A.J, Springer.

Thagard, P. (2006). Hot thought: Mechanisms and applications of emotional cognition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Thagard, P. (2010). “EMPATHICA: A computer support system with visual representations for cognitive-affective mapping”, in K. McGregor (Ed.), Proceedings of the workshop on visual reasoning and representation (pp. 79-81). Menlo Park, CA: AAAI Press.